School Administrator Magazine

AASA's award-winning magazine provides big-picture perspectives on a broad range of issues in school system leadership and resources to support the effective operation of schools nationwide.

Current Issue

School Administrator: Politicization in Public Schooling

Advertisement

Previous Issues

-

September 2024: School Administrator

September 2024: School AdministratorThis issue covers a new age of public schools and education leadership amidst ongoing culture wars.

-

August 2024: School Administrator

August 2024: School AdministratorThis issue tackles several important topics facing educators today, ranging from the two design principles for helping students living in poverty, expanding computer science offerings and delaying high school start times.

-

July 2024: School Administrator

July 2024: School AdministratorThis digital-only issue compiles articles and columns of the past year examining changing mindsets, superintendent mental health and the importance of data privacy and cybersecurity and much more.

-

June 2024: School Administrator

June 2024: School AdministratorThis issue examines how school districts can modify attitudes about cellphones in schools, staff training and inclusion of all children with disabilities to improve teaching and learning experiences.

-

May 2024: School Administrator

May 2024: School AdministratorThis issue examines several solutions and strategies to help school districts hire and retain teachers amid ongoing staff shortages.

-

April 2024: School Administrator

April 2024: School AdministratorThis issue examines how school districts can modify behavioral and operational practices to account for climate change.

-

March 2024: School Administrator

March 2024: School AdministratorThis issue examines the rise of the four-day school week and the digital learning landscape in the aftermath of COVID-19.

-

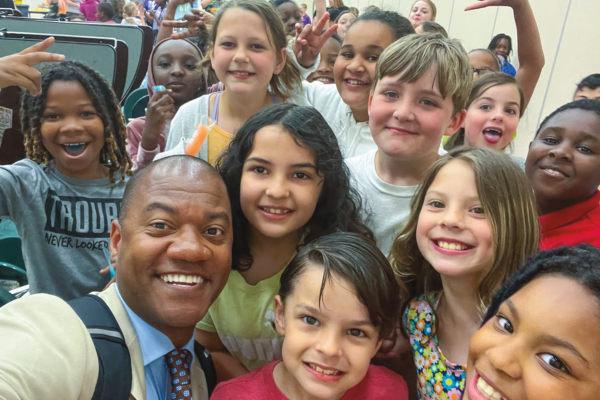

February 2024: School Administrator

February 2024: School AdministratorThis issue examines how superintendents are defending their school districts from cyberattacks and protecting their students’ data.

School Administrator Staff

Advertise in School Administrator

For information on advertising with AASA, contact Kathy Sveen at 312-673-5635 or ksveen@smithbucklin.com.

Advertisement

Advertisement