Public Schools as Contested Places

February 01, 2023

Health practices, racial equity initiatives and school library holdings move into the heated center of cultural conflict, raising pivotal considerations for leadership

This past fall, I met with a small group of school superintendents in Murrieta, Calif., a suburban community in Riverside County, about 90 minutes from my home in Palm Springs. Tim Thompson, a local evangelical pastor in that part of the county, has described the public schools there as “the devil’s playground,” and he decided to support seven candidates for election in three of the area’s school districts.

In one district, the pastor promoted a slate of four candidates on a five-person school board. I asked the superintendent of that district what would happen to her efforts there in supporting equity and reducing inequality among her students if the pastor’s slate were to be elected. She answered: “They would be gone instantly!”

In the November election, much to the surprise of the education establishment, five of the seven candidates supported by the pastor’s Inland Empire Family PAC won seats on the school boards in that part of Riverside County. On his group’s website, Pastor Thompson declared: “I am positive that together we can restore parental rights in our schools and be a force for truth and transparency in education. I truly believe the conservative voice will become the dominating force in California politics.”

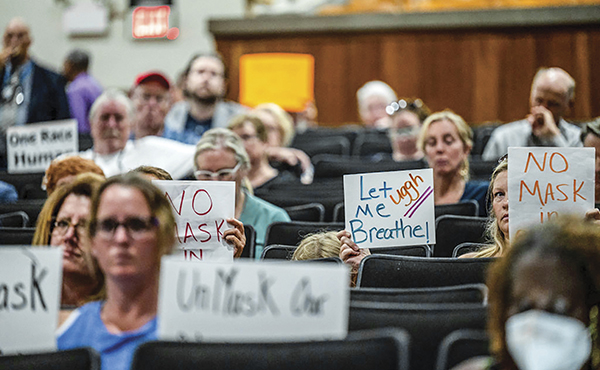

This is just one example of the growing polarization in America that makes our public schools and school districts contested places on a wide variety of fronts. For almost three years now, the pandemic put an extraordinary spotlight on public education in local communities in ways that were unprecedented. Public health and mask mandates were put under close scrutiny and questioned harshly. The pandemic also opened a unique window into curricular content that has shined intense light on social emotional learning, along with schools’ diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder and the inevitable reckoning that followed.

Beyond curricular content, an intensified examination of school library books is underway in many school communities with most observers who are old enough recognizing that book banning is not a new phenomenon in America.

Well-Organized Forces

What is new regarding America’s public schools, however, is their centrality in these new culture wars. Mark Davis, the conservative host of a national AM radio program emanating from Dallas, Texas, wrote in a post on the Townhall social media platform: “In normal times, a slate of school board candidates should be sifted for evidence of good character, fluency in educational issues and a worthy resume. Those remain important, but the evaluation of school board candidates must now contain a vital element: a clear, unapologetic willingness to block the racial and sexual fanaticism that threatens education at every level.” He went on to say without evidence that “we have teachers indoctrinating elementary schoolers into believing that they may choose their genders from a vast menu of debauched choices hatched in the minds of militants.”

What seems to be emerging in our nation’s contested public schools arena today is the very opposite of the late House Speaker Tip O’Neill’s famous dictum that “all politics is local,” to rather what New York Times columnist David Brooks recently suggested: “All politics is now national.”

At a national convening that I co-hosted last summer of school superintendents, scholars on the politics of education and leaders of superintendent preparation and support, several researchers argued that equity-minded school leaders need to be aware that right-wing forces in America today are much better organized than progressive forces and that the right is playing by new rules that superintendents and their allies have been reluctant to embrace in the past. (The conference was sponsored by the William and Flora Hewlett and WT Grant foundations.)

Most superintendents have viewed school board elections as nonpartisan and have not endorsed candidates for their boards. However, five states (Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Tennessee) now allow partisan local school board elections, with Indiana, South Carolina and West Virginia hoping to join them soon with active bills favoring partisan school board elections under consideration in those state legislatures.

Some conservative governors, such as Ron DeSantis of Florida, are not waiting for legislative action but have started endorsing candidates in local nonpartisan school board races even though a 1988 constitutional amendment in that state bans partisan local school board elections.

DeSantis endorsed a combined total of 30 candidates in local school board elections around the state in both the August primary and the November runoff. Twenty-four of his candidates won, including the high-profile ouster of a 24-year incumbent on the board in Miami-Dade, the country’s fourth largest school system. DeSantis-backed candidates all committed to a platform of school choice, parental rights, abolition of critical race theory and ending discussion of gender identity in the early grades. According to the Miami Herald, DeSantis said at an election night victory party: “Florida is the state where woke goes to die.”

In Sarasota, Fla., where a DeSantis-backed slate became the new conservative school board majority, the winners were quick to downplay and deny the involvement of the Proud Boys in their get-out-the-vote effort, even though members of the far-right extremist group were photographed at the victory party flashing white power signs, according to the Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

That new board majority, however, wasted no time in November to oust its superintendent of two years, Brennan Asplen, even though the Sarasota district had earned A ratings from the state both years, according to Politico. Asplen was one of two Florida superintendents forced out by new board majorities immediately following the mid-term elections. Another superintendent, Deon Jackson of Berkeley County in South Carolina, was removed by a new board majority, even though he had no performance issues raised by the previous iteration of the governing body.

These new developments in school board politics in America are the result of focused efforts by conservative activists going back to at least the decade of the 1990s when Ralph Reed, head of the Christian Coalition, first said: “I would rather have a thousand school board members than one president and no school board members.” In the Trump era, conservative media provocateurs like Steve Bannon are sounding a very similar call to action that is designed to gain power and influence from the bottom up in one of the most critical areas of government influence: the control of K-12 public education.

It’s also important to point out that these new efforts are being fueled by conservative dark money resources in several states, including Florida, Texas, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Ohio and Arizona, according to Politico. Four of the most prominent are Moms for Liberty, FreedomWorks, the New York-based 1776 PAC and the Restoration PAC. Their stated agenda includes restoration of parental rights, abolition of CRT and a ban on gender identity indoctrination.

Critical Questions

Several important and difficult questions now face equity-minded superintendents and school board members as this phenomenon of schools and districts as contested places unfolds across America. Chief among them are these three:

Should the rhetoric around promoting equity and reducing inequality be paused, slowed, muted or less publicized?

Can progressive parents and community members and their superintendent allies come up with new strategies and tactics to beat back the well-positioned forces on the right arguing that today’s public schools are disconnected from pro-family parents and their values?

Should superintendents rethink their long-held practice and tradition of remaining nonparticipants on the sidelines of local school board elections?

Acting Without Fanfare

When I was working with the board and superintendent of a suburban district of 8,500 students in California recently, I suggested the rhetoric and resolutions around equity be toned down in favor of simply implementing programs that reduce inequality without a lot of fanfare and moral posturing. One of the school board members pushed back hard against my suggestion, saying, “I want to flush out all of these racists in our community, and I don’t want to tone down our approach at all.”

That board member’s approach might be acceptable if he is certain about future electoral outcomes in all school board races in that community, but if that stance triggers the forces of the right to start mobilizing resistance and fielding school board candidates of their own, perhaps with outside financing, what has that posture done for historically underserved students who need real programs and services to address their needs right now?

When I was a first-year superintendent in Long Beach, Calif., back in the early ’90s, I was asked by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges to chair an accreditation visit for the adult school program at the federal prison on Terminal Island, which is about 10 minutes from Long Beach. There is nothing more sobering for a new superintendent than spending three days in a prison where you get an up-close and personal look at what happens to males of color if they don’t get a decent basic education.

When I asked the inmates to describe their K-12 schooling experience, 90 percent of them said they never really learned to read, and they ended up being socially promoted without that requisite skill. Many dropped out of high school when it became clear they couldn’t read their textbooks and that going to school was a waste of time if they couldn’t do the high school work. They dropped out without job prospects or academic skills, leading to their initial embrace of illegal activities and subsequently a life of crime.

I left that prison shaken but determined to lead a school system that would do better by the young males of color in my hometown of Long Beach.

In our focus on early literacy, we decided to give all 3rd graders not reading at grade-level six weeks of free summer enrichment focused on literacy. We had each student sit with a teacher who assessed the child’s literacy level using a benchmark book. When I asked our stellar assistant superintendent of research which youngsters were likely to end up in our new summer program, she indicated without hesitating that it would be 80-90 percent males of color, and she was absolutely right. However, we didn’t adopt a school board resolution suggesting this was our commitment to equity or reducing inequality. We just did it without fanfare, never flagging that our commitment to the importance of rescuing kids grew out of our own moral superiority.

These and other initiatives over a 10-year period led to Long Beach winning the 2003 Broad Prize for Excellence in Urban Education without a paper trail of school board resolutions, adopted equity plans or suggestions about our embrace of the moral high ground. In today’s politically contested school environments, there may well be some valuable lessons learned from that Long Beach experience of flying under the radar and doing the work successfully on behalf of historically underserved students.

Fighting Back

In November 2021, progressives across the country were surprised and dismayed when Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin of Virginia handily won the governorship there largely through a successful appeal to white suburban voters, who a year earlier had supported Joe Biden for president. Youngkin argued that something had gone terribly wrong with the public schools and that he singlehandedly intended to change that. He intended to ban critical race theory, mask mandates and classroom-based discussions of gender identity, while restoring parental rights to their appropriate role in determining what goes on in local public schools.

In that same election, conservatives scored a complete sweep of the school board election in Douglas County, Colo., where mask mandates and schools closed for too long during the pandemic were the driving issues. According to the Denver Gazette, one observer described the outcome as “a tsunami of parent power” in taking back control of the local public schools. The ouster of the equity-minded superintendent soon followed the school board takeover.

In 2022, however, progressive forces led by parents are fighting back in other battleground states and winning. Wisconsin and New Hampshire are two recent examples of places where well-organized efforts are paying dividends in not ceding control of school boards to right-wing groups.

John Nichols of The Nation described a heroic school board candidate in Eau Claire, Wis., who, after receiving a death threat directed at both him and his entire family because of his alleged support of transgender students’ rights, put out the following message to the entire community: “Others want to control this election by inciting fear in you and driving votes with outside money and news coverage. They, quite literally, are trying to threaten us into submission. I remain unbowed. And I implore each of you to send a message that Eau Claire cannot be intimidated. Our schools are too important to cede to fear.”

On election day two weeks later, that candidate came in first and his progressive slate prevailed as well against better-funded conservative candidates.

The often-red Granite State of New Hampshire provides even more encouragement to progressives wanting to organize and ensure that local school boards don’t become the exclusive domain of right-wing forces bent on control of local public schools. The local school board elections in that state last spring were hailed as the “great reckoning” for all the pandemic wrongs in the schools, as well as their preoccupation with CRT, gender identity, diversity and other “woke” evils. According to this political narrative, voter frustration was running so high that voters were prepared to embrace full-blown voucher schemes that would direct public school money to parents to spend at any school they wanted, including private and parochial schools.

But a funny thing happened on the way to this predicted conservative sweep of local school board elections as a precursor to a Republican sweep in the fall mid-term elections. Not only did it not happen, but progressive forces fielded candidates in many traditional red areas of the state and won handily by arguing against extremism in the public schools.

Election Involvement

Historically, superintendents have steered clear of their local school board elections, neither endorsing candidates nor contributing to campaigns in what seemingly have been nonpartisan local elections, where the notion prevails that children come from families that are Democratic, Republican, Independent or whatever. Superintendent preparation programs and leadership associations, such as AASA, the Council of Chief State School Officers and the Council of Great City Schools, largely have endorsed a nonparticipatory stance when it comes to local elections.

A hard-working and dedicated superintendent in Virginia recently said to me: “The only thing worse than having the Barbarians at the gates of my district will be having two of them duly elected to the board and sitting on the dais making policy.” This is the reality that superintendents are facing in America today in both red and blue states. And the greatest threat isn’t around the superintendent keeping his or her job but the progress being made for real students on the fronts that promote equity and reduce inequality in schooling that could be lost.

In all candor, I must confess that I did not stay out of school board elections during my 10-year run as superintendent in Long Beach. I fully endorsed and supported candidates for the school board, which would always trigger an editorial headline from my local newspaper saying: “Carl Cohn is trying to pick his bosses.”

The truth is, that editor of the local newspaper was a good friend who was overwhelmingly supportive of the work we were doing to improve student performance in the district but, as a good journalist, he also felt compelled to call out and not ignore a public servant with a glaring conflict of interest. I always responded with good humor that I thought it was patently unfair to silence only the superintendent when all other employees of the district got to “pick their bosses” through their union’s involvement in school board elections.

My successor, Chris Steinhauser, who had an extraordinary tenure of 18 years following my decade, also endorsed candidates for the board. Our collective effort has, in effect, brought three decades of leadership stability to a large urban district that has been recognized nationally and internationally for consistently moving the needle on student performance — a singular accomplishment that can’t be ignored as we evaluate today’s current climate of schools and districts as contested places.

At a minimum, I think we need a national conversation between superintendent and school board leadership (through both the National School Boards Association and the Consortium of State School Boards Association) about the path forward and what the new norms ought to be about the rules of engagement and the changing role of superintendents in today’s highly polarized political environment of local school board elections. The needs of historically underserved students are too great to ignore or delay this important discussion and debate.

Carl Cohn, a retired superintendent, is professor emeritus and senior research fellow at Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, Calif. @carlcohn

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement