Spotlighting Student-Centered Learning in Four School Systems

January 01, 2026

Aiming to raise engagement by giving students greater say in what and how they are studying

Colorful, hand-drawn backpacks line classroom walls in California’s Campbell Union School District. The outside of each backpack is decorated with symbols that represent parts of a student’s identity that can easily be seen. The inside, revealed by opening two paper flaps, discloses vulnerable thoughts or perceived flaws.

One 5th-grade student’s backpack has smiley faces and hearts on the outside, with this interior message: “Some rarely see me without a smile. … On the inside, I often feel like I’m forced to be happy.”

The project, titled “The Weight We Carry,” helps students elevate their voice and agency while learning about inclusion and acceptance and speaks to the core of student-centered learning.

“There’s a lot of evidence like that of teachers making it OK to be different,” says Shelly Viramontez, superintendent of the district, which is based in Santa Clara County and serves 6,000 students in pre-K through 8th grade. “We’re not the same, and that makes us better.”

This Content is Exclusive to Members

AASA Member? Login to Access the Full Resource

Not a Member? Join Now | Learn More About Membership

Author

A District’s Microschool Brings an Innovative Academic Lab

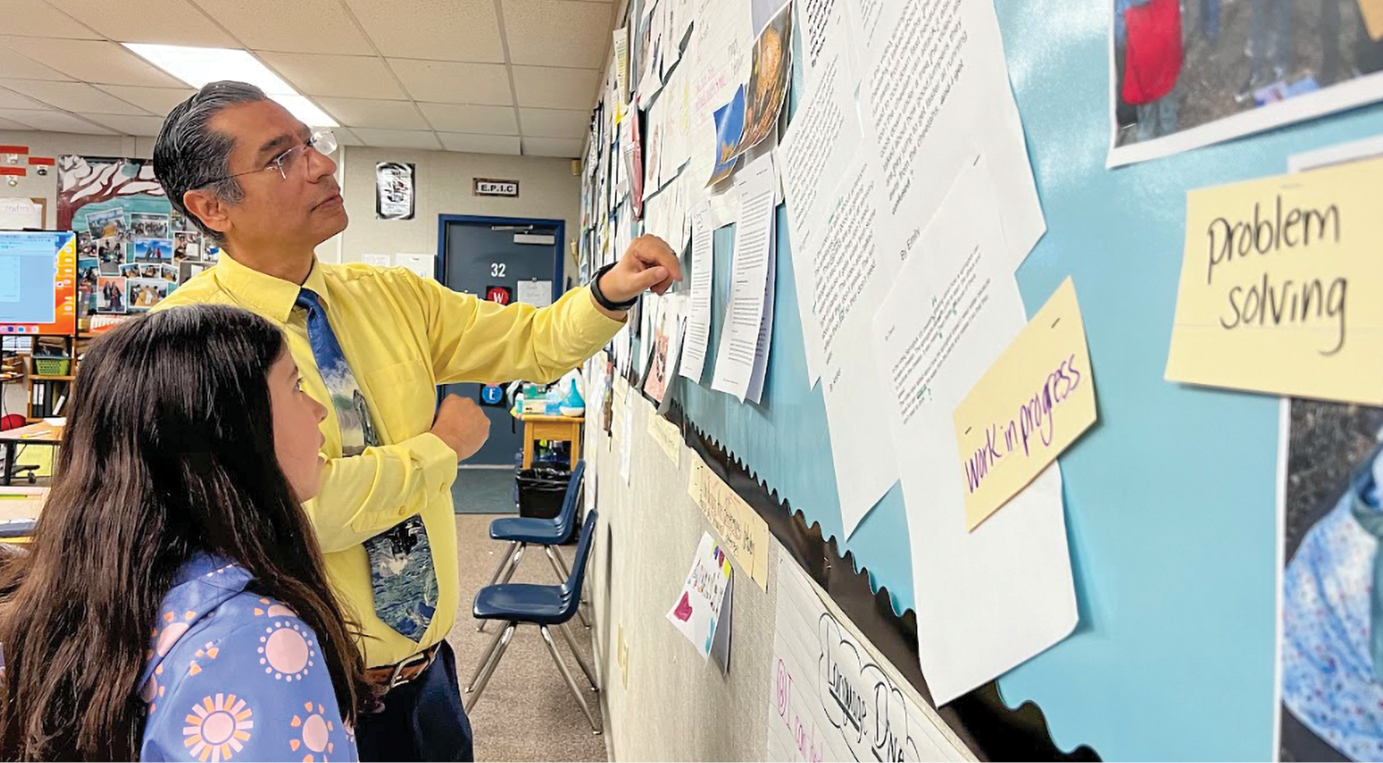

The Escondido Union School District in southern California was seeking new ways to spark innovative student-centered learning a few years ago.

The district believes it has found a useful model by creating the HV Microschool, an academic laboratory of sorts for testing techniques to better engage students. Opened in fall 2024, the small-scale learning environment operates in a dedicated space within Escondido’s Hidden Valley Middle School.

Each of the microschool’s 160 students in grades 6 through 8 “were intentionally identified through an inclusive process that ensured representation from all learner groups,” says principal Bryanna Norton.

The students belong to a small, close-knit group assigned to four core teachers. They’re regularly asked what they like about what they are doing in school, what they don’t like and what their learning wishes are. Every morning starts with an advisory class, where students participate in community circles for social-emotional well-being before setting a weekly goal for their academics or behavior. Afternoons end with a wellness class, which provides space for discovering individual strengths, purpose and potential directions.

“The kids should be empowered and have a voice in what they do,” Norton says.

Gaining Interest

The National Microschooling Center, based in Las Vegas, has seen interest in microschools from public school district leaders double in each of the past two years, according to Don Soifer, CEO and co-founder.

The concept, he says, is “popular right now and very much in the early adoption phase.” The center is actively advising leaders from two dozen public school districts. Some superintendents are in the conceptual stage, while others have plans for design and implementation that vary considerably, adds Soifer, who recommends adhering to the center’s nine principles for microschooling posted on its website. (They include “Microschools exemplify responsiveness” and “Microschools are communities built upon authentic relationships.”)

While microschools most often are found in independent and charter schools and other nontraditional spaces, “they’re an on-ramp to evolution in public school systems that already have the infrastructure,” says Learner-Centered Collaborative CEO Devin Vodicka, a former superintendent who has been creating, launching, implementing and iterating microschools for more than a decade. Supported by a grant from Getting Smart Collective, a learning design firm, his nonprofit organization supported the launch of three microschools in the 2024-25 school year, including HV Microschool.

Learner-Centered Collaborative and two other nonprofits, Getting Smart and Transcend Education, collaborated on The Public Microschool Playbook, a free resource created in May to help school districts with planning, designing and implementation.

Trying New Ideas

The idea for HV Microschool came out of an initiative to redesign every school in the 14,000-student Escondido Union School District. That initiative was interrupted by the pandemic, but once back on track, there was newfound “permission to think outside the box,” given the number of reinventions that had to take place post-2020, says superintendent Luis Rankins-Ibarra.

“Sometimes our barriers were our systems, and we blew up the system,” he says.

Word about the HV Microschool has spread. Partnering with consultants from Learner-Centered Collaborative, Norton, the principal, hosts visits by superintendents from around the region and has been invited to present at public sessions.

The district will launch another microschool at the elementary school level in 2026-27.

When starting a district-operated microschool, Norton suggests looking for educators “who are early adopters and innovators who feel really comfortable trying new things and seeing what works — and what doesn’t work.”

Lesson Sharing

Lessons from the microschool’s early experiences are shared with teachers in Hidden Valley Middle School’s traditional classrooms during schoolwide staff meetings, department meetings and grade-level meetings. Those teachers have permission to try out the test site’s innovative methods, but there’s no pressure to do so unless they lead to schoolwide adoption.

That’s the purpose of this small-group experimentation. That is, until the buzz the district is trying to create leads to even more demand.

“The reality is the microschool will continue to grow larger,” says Rankins-Ibarra, “until the innovation just swallows the entire school.”

— Robin Flanigan

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement