The Power of Purposeful Transitions

February 01, 2026

When a superintendent moves into a new community, the goal ought to be to lead with clarity and compassion

The first time stepping into a superintendent’s role can be overwhelming. In my own first transition, I was fortunate already to know the community, which meant I could focus entirely on learning the job. That experience taught me something I have carried into every role since: In a leadership transition, you can truly only learn one big new thing at a time.

Over the course of my career, I have navigated five superintendent transitions across rural, suburban and urban communities. These districts have ranged from fewer than 3,000 students to more than 25,000, and they have spanned multiple states. Each move has been its own laboratory for leadership with different cultures, expectations and systems, yet all have shared a common truth: The way a leader enters shapes the story that follows.

That one new thing changes depending on the move. Transitioning within the same school district means the relationships and culture may already be familiar, allowing a sharper focus on mastering the role. Moving to a different and unfamiliar district, especially from rural to urban, can be an entirely different experience. The job may be the same, yet the pace, politics and priorities feel worlds apart.

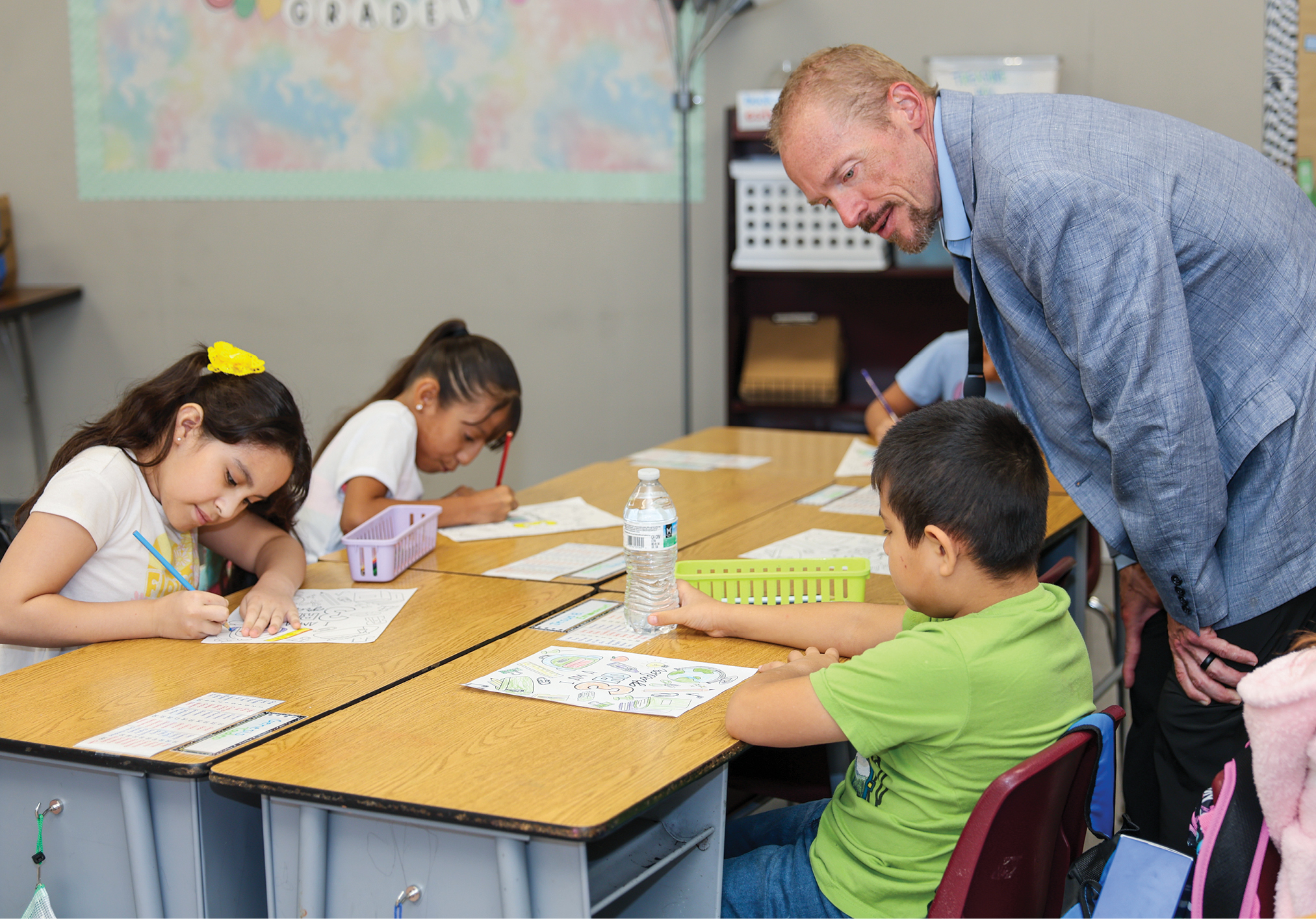

In every case, beginning with deep listening communicates something powerful. It reveals a leader’s posture, shows whether they value their own expertise over the wisdom of the community and signals humility and situational awareness, which is the ability to lead with a light touch while taking in the full context.

Authenticity is equally critical. Adopting a style that does not reflect a leader’s true nature creates a false expectation that will eventually erode trust. Transitions also reward restraint. By resisting the urge to immediately fix problems, a leader can observe how the system operates naturally, notice who the true influencers are and uncover where pockets of genius already exist.

The first focus in any transition should be on people. In the early months, it is more valuable to talk about what is wanted for them than what is expected from them. That might mean helping them build the best team of their professional life, ensuring they feel their work has a lasting impact on students or fostering a sense of genuine empowerment. Paying attention to the stories, heroes and myths that circulate helps uncover the DNA of the culture — and understanding that culture is the foundation for leading well.

Mindset for Purposeful Transitions

Leadership transitions require an unusual blend of confidence and humility. I often remind leaders that as the area of knowledge increases, so too does the perimeter of ignorance. Picture all the books you have read on leadership, governance and finance filling the shelves of your office. Now picture the “anti-library,” all the books on those same subjects you have not yet read. There is always more to learn, and the knowledge brought into a new role comes from a different district with its own context. Leaning too heavily on that prior experience risks creating a narrative that sounds like, “If you liked it so much there, maybe you should go back.”

A powerful discipline in transitions is the ability to slow down. Aside from matters involving safety or legal compliance, few decisions must be made urgently. In one of my superintendent transitions, every cabinet-level position became vacant. The temptation to fill them quickly was strong, but slowing the process allowed for a deeper understanding of the system and for finding candidates who were both skilled and the right cultural fit.

In one of my earliest transitions, staff members repeatedly told me they were struggling with discipline issues. Had I relied on my previous district experience, I would have read this as a need for clearer expectations or stronger systems of classroom management. When I slowed down and listened across groups, a very different signal emerged.

The real issue was transportation. Buses arrived late every day because the district was using an outdated routing program. Students were starting their mornings already frustrated, and teachers were beginning each class period in recovery mode.

The solution had nothing to do with discipline at all. Updating the routing software and adjusting schedules reduced student referrals by nearly 30 percent within a semester. Listening first saved us years of chasing the wrong problem.

Knowing when to act comes from attentive listening. In the first 100 days, asking just two questions — “What do you love about the district?” and “What would you have me focus on?” — yields a wealth of information. In information theory, this is the difference between “noise” and “signal.” Noise is not inherently bad, but the leader’s role is to detect the signal, meaning the recurring themes that emerge across diverse groups.

One tool that can help leaders navigate transitions is the “recipe card.” Just as a chef relies on a recipe to combine ingredients in the right amounts and sequence, a leader can use a recipe card to guide the steps of a transition. There are two worth keeping: one for entering a district and one for leaving. The entry card begins with people and curiosity, then gradually mixes in communication, followed by visibility and finally accountability when the timing is right. (See related article, above.)

Trust, Clarity and Culture

A leader enters a new role with a no trust bank. Trust must be earned from the first day and even before. The most effective way to build it quickly is through intentional, consistent communication. Be specific about what is being done and why and communicate that across all audiences (board, staff, community and students).

Trust grows through visibility and transparency. Share your calendar with school board members so they see who you are meeting with. Spend time on campuses regularly, and follow up on conversations. Communicate intentions, actions and follow up. When it feels like you have said it enough, you are just getting started.

Explaining the “why” behind change is particularly challenging when it disrupts longstanding norms. The instinct may be to declare the need and point to students or teachers as the reason. Instead, tell a story. A story about a credit recovery student caring for a baby at home and feeling unsupported allows listeners to step into the experience. Once they are in the story, a simple question, “Does this matter?” opens a far richer conversation.

Reading a district’s culture accurately is both art and discipline. Missteps are inevitable. Applying the framework of a previous district to a new one can spark needed innovation in some areas and create disruption in others. The goal is to amplify the innovation while minimizing chaos. Look for alignment between what you see, what you hear and what the numbers reveal. If all three point toward a need for change, lean into it.

Quick Wins vs. Long-Term Goals

The pressure for visible results is intense. A well-chosen quick win can help build momentum. In one of my district transitions that followed Hurricane Harvey in 2017, a nearly year-long stalemate with the insurance company was draining resources and morale. Sensing deliberate stalling, I made the early decision to pursue legal action. Communicating this intention clearly and often helped build trust even before the case was resolved.

The danger lies in misreading the problem. As Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linsky, co-authors of The Practice of Adaptive Leadership, share, technical problems have known solutions, but adaptive problems require shifts in values, beliefs and behaviors. Treating an adaptive problem as a technical one leads to the “whack-a-mole” cycle where it reappears in different forms. In reality, there are few true quick wins in a transition.

Long-term success comes from a vision co-created with the community. Early actions should bring that vision into focus for everyone. Every leader leaves a legacy, and it begins forming in the first hour of the first day. Aligning early actions with that long-term vision ensures the legacy will be lasting rather than fleeting.

Redefining Success

Creating a shared definition of success cannot be done for a community or to a community. It must be done with them. That means meeting in every setting possible, listening to every voice and using tools that widen participation.

In a suburban transition, I held a student focus group early in the first 100 days. I expected conversations about course offerings, extracurriculars or lunch options. Instead, student after student said some version of this: “We do not know what this district wants for us.” They were high performing on paper, yet deeply unclear about the district’s purpose. Their comments revealed a vision vacuum that adults had not acknowledged.

This became the signal. We launched a strategic plan refresh anchored by a newly created Profile of a Graduate. When the community saw their own themes reflected (responsibility, empathy, communication and perseverance), momentum grew quickly. Students were right. The district did not need new programs. It needed a shared direction.

The process begins with openness. Sharing beliefs, hopes and dreams at the outset helps others better understand the leader and primes them to share their own. When the vision is built this way, ownership is baked in from the start.

The first challenge is often moving beyond a narrow definition of success, such as test scores. While academic results matter, students are far more than a number. A profile of a graduate offers a broader view of the skills, mindsets and values a district wants for every student. Building assessments tied to this profile creates richer conversations about both students as learners and as people.

The Graceful Exit

Most leaders focus on starting strong. While understandable, this can signal that the previous role was merely a step toward something else. Entering a position with a sense of duty, hope and vision comes with the obligation to pass that forward to the next leader. Both the district being entered and the district being left deserve full commitment.

Leaving well starts with stories. Invite people to share the moments and accomplishments that matter most. Finish projects. Have final conversations. Continue to talk about what you want for them. For me, the most important thing to leave behind is hope for a better future, hope they can accomplish hard things, hope that lights the soul on fire.

The best leaders know they are not the star of the show. They are the host of an experience. That perspective shapes the exit as much as the entry. The transition becomes something to coordinate thoughtfully with the incoming leader, asking three questions: How do we want people to feel? What do we want them to think? What do we want them to do?

Closing Thought

Every transition is a doorway, and every doorway swings in both directions. How you enter determines your impact in the present. How you leave defines your legacy for the future. The measure of a leader is not just in the way they step into the room, but in the way they make it better for everyone after they are gone. n

Quintin Shepherd is superintendent of the Pflugerville Independent School District in Pflugerville, Texas.

Author

Recipe Card for a Smooth Transition

In educational leadership, a “recipe card” is not for the kitchen. It’s for the critical first steps in a leadership transition. The idea, passed along to me by a professional coach many years ago, is that every superintendent should have a go-to sequence of actions that can be adapted for any school district. The order matters. The proportions matter. The goal is to combine the right elements, at the right time, to create the right conditions for change.

A steady pour of vision, co-created with the community

- Begin by combining curiosity with listening. Blend eyes, ears and data until the mixture is rich with understanding.

- Fold in humility, being careful not to over-stir. Humility should remain visible in the final result.

- Slowly add visibility and communication, alternating between the two until well-integrated.

- Sprinkle in capacity analysis to see where the organization is strong and where it needs strengthening.

- Add the “keep or discard” step, removing what no longer serves the mission and keeping what works.

- Stir in the genius, uncovering and celebrating the strengths already within the organization.

- Season with a healthy data culture, where information is shared openly and used to drive improvement.

- Pour in vision, co-created with the community, as the final ingredient. Let it infuse the entire mixture.

- Serve immediately by modeling these behaviors every day. Adjust seasonings as needed based on feedback, culture and context. This recipe works in any district, but the flavor is always shaped by the local ingredients you discover along the way.

— Quintin Shepherd

The First 100 Days: A Blueprint for Listening and Learning

A strong start as a superintendent is less about making sweeping changes and more about building a foundation of trust, understanding and shared purpose. A focused 100-day plan can serve as the blueprint.

I have been refining mine since my first transition, customizing it for each school district and sharpening its intent over nearly two decades of practice.

Begin with listening.

Start with the two questions that unlock the community’s perspective: What do you love about our district? What would you have me focus on? Ask them in every setting possible: small groups, large gatherings, student focus groups, parent meetings and community forums. Use both in-person and online tools to ensure every voice can be heard. The benchmark goal is 100 percent access.

Build relationships across the system.

Make it a priority to visit every school, meet every principal and engage directly with teachers, staff and students. Spend time with PTOs, booster clubs and student leadership groups. These conversations not only reveal the district’s culture but also identify the unsung heroes and informal leaders who make the system work.

Connect with the wider community.

Meet with business leaders, nonprofit directors, civic groups, faith-based organizations and elected officials at the city, county and state levels. Establish clear, routine communication channels with these partners. The goal is to form an interdependent network of support for students and schools.

Align with the board.

Revisit the school district’s vision, goals and board operating procedures together. Clarify roles, responsibilities and expectations. Establish regular communication with the board president and schedule retreats or training sessions to strengthen the “Team of 8” dynamic.

Assess the current state.

Review student achievement data, instructional practices, curriculum alignment and special programs. Examine operational systems such as technology integration, resource allocation and administrative processes. Use a SWOT analysis to identify assets, barriers and opportunities for improvement.

Communicate transparently.

From the start, be intentional about telling the story of your entry into the district. Share your calendar with trustees, report progress regularly and highlight what you are learning. Visibility builds trust.

Deliver a findings report.

At the conclusion of the 100 days, present your findings to the board and community. Outline the signals you have heard, the strengths to build on, and the challenges to address. Use this moment to frame the next phase, whether it is a strategic plan refresh, targeted initiatives or long-term goal setting.

The first 100 days are a leader’s opportunity to set the tone for the years ahead. Lead with curiosity, connect with people before focusing on programs, and let the community see that their voices are shaping the district’s direction. A deliberate, disciplined entry creates the trust and clarity needed for every step that follows.

— Quintin Shepherd

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

.png?sfvrsn=3d584f2d_3)