Navigating Discussions of Race and Class

April 01, 2022

A superintendent’s candid self-reflections of how it all played out in his Missouri district through the use of an after-action review

In 2015, Columbia, Mo., received national attention when protests about racial justice erupted on the campus of the University of Missouri. Both the university president and chancellor resigned from their positions, and school districts across the state

began developing or strengthening their equity programs.

During this time, I was in my second year as the superintendent of a district of 19,000 students with urban, suburban and rural characteristics based in Columbia. The events on the

university campus and in the local community became a turning point in our equity work — from discussions about socioeconomics to an emphasis on race. But it wasn’t immediate or easy.

After a district-run professional training

course on the history of Black Lives Matter (including discussions on how to respond to comments such as “well, I think all lives matter”), we were advised by our county’s emergency management center of an unusual 9-1-1 call:

Dispatcher: 9-1-1. How can I help you?

Caller: I am calling because I want this stopped.

Dispatcher: This is 9-1-1. Is there an emergency?

Caller: Yes, my wife was forced to attend a training, an equity training, and she was told to feel guilty for being white.

Dispatcher: I am sorry sir, but this is 9-1-1.

Caller: I know it’s 9-1-1. This is an emergency.

Dispatcher: When did this happen, sir?

Caller: Yesterday.

Dispatcher: Yesterday?

Caller: Yes, my wife went to a district training yesterday and learned about Black Lives Matter.

Dispatcher: Sir, this is 9-1-1. This number is for calling in emergencies. Goodbye.

This Content is Exclusive to Members

AASA Member? Login to Access the Full Resource

Not a Member? Join Now | Learn More About Membership

About the Author

Peter Stiepleman retired as superintendent in Columbia, Mo., last June.

Model for Human-Centered Transformation

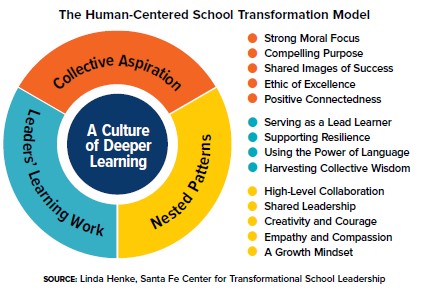

When I am asked to describe the leadership model I believe in the most, I turn to what I consider the most complete model: the Human-Centered School Transformation Model created by the Santa Fe Center for Transformational School Leadership.

The model has three trailheads, all of which lead to a place where everyone is honored and valued, where everyone plays an important part. It leads to a culture

of deeper learning. It offers a different way to think about leadership. It asks you to consider the why, the what and the how of leading. Those three trailheads are known as collective aspiration, nested patterns and leaders’ leading work.

Collective aspiration makes sure everyone in the organization is on the same page and that everyone is working toward the same goal. If we all aspire for the same thing and share the same understanding of what success looks like, then it is

more likely we will succeed. Collective aspiration is the heart of everything that is done. When someone is unclear as to why a decision has been made or an approach is being considered, collective aspiration serves as the why.

Nested patterns

are the behaviors of everyone in the organization and describe the behaviors that are valued. Nested patterns include people working together and collaborating. They include sharing leadership responsibilities and emphasizing the importance of creativity,

courage, empathy and compassion. Nested patterns are the trailhead that challenges individuals to be critical about the way they’ve always seen the world (growth mindset).

In the Human-Centered School Transformation Model, nested

patterns are the muscle of the work. Just as a musician or an athlete practices and practices so their motions become automatic, leaders who learn these nested patterns understand what it means to lead. Nested patterns are important when things are

going well, and they are essential when things are not going so well.

Leaders’ learning work is where core processes and practices can be found. It is where we are reminded of the fundamentals of leadership. For one, that leadership

is about showing others you’re willing to admit you’ve made a mistake and then showing how you’ve learned from those mistakes. It is also about using everyone’s ideas to design a better way of doing things and adjusting those

systems when necessary. And it is being able to communicate ideas in a way that everyone can understand. Leaders’ learning work is the how, the brains of the work.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement