Failure and Recovery

August 01, 2020

Life after a school system loses accreditation is a slippery slope for school leaders who face three major groups of stakeholders in the process: the educators they lead, the communities they answer to and the students whose lives they impact.

Even for the most accomplished education leaders who are focused on continuous improvement in their schools, the stigma attached to lost or marginal accreditation is a powerful force to contend with while working to regain footing, funding and faith.

School leaders who faced these predicaments in Georgia and Missouri discussed the depth and breadth of the problem and its solutions, which in turn gets to the heart of why accreditation by outside agencies is sought after in the first place.

“Every educational institution should put its students first, and accreditation helps hold people accountable as servants of the people,” says Art McCoy, superintendent in Jennings, Mo. Adds Morcease Beasley, superintendent in

Jonesboro, Ga.: “Accreditation lends credibility to your work.”

Both Jennings and Jonesboro have bounced back from the disappointment and disruption that resulted when those school districts lost their accreditation status.

This Content is Exclusive to Members

AASA Member? Login to Access the Full Resource

Not a Member? Join Now | Learn More About Membership

Author

Using Accreditation to Boost High-Poverty Schools

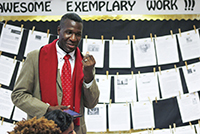

At the back-to-school celebration in Jennings, Mo., six years ago, then-superintendent Tiffany Anderson announced preliminary test scores that guaranteed the high-poverty suburban district would regain full state accreditation, a goal that had been elusive

for years.

Anderson told the educators in a packed auditorium that the milestone had far-reaching implications beyond the school district in north St. Louis County and its 3,000 students, 96 percent of whom qualified for federally subsidized

lunches. The success in Jennings, she announced, is “giving hope to every district that looks like us.”

That includes the high-poverty Topeka Unified School District 501 in Kansas, where Anderson was hired in 2016 to lead 30

schools and 14,000 students.

External Buy-in

The high-performance bar for effective schools is aided, she says, by an accreditation and/or continuous school improvement process that the community sees as a shared experience, with support for programs, policies and procedures that help students and

families overcome barriers that prevent a deeper school engagement.

Poverty-fighting measures include working with local food banks to open onsite and mobile pantries; placing washers and dryers in schools, where the cost per load is one

hour of community service; offering comprehensive, school-based health care; providing shelter for homeless and foster children; expanding after-school programming; and monthly data checks to track and review student progress, attendance, finances

and social-emotional well-being.

“When you go to the doctor, you’re sitting on the bed, they take out a computer and pull up your health history,” Anderson says. “There’s no difference here. We pull up a child’s

academic health history.”

None of this is possible, she explains, without strong community buy-in and partnerships with key players, including businesses, colleges and universities.

“Galvanizing the community around

the success of students in the name of accreditation, or continuous improvement, or whatever you want to call that,” Anderson says, “it’s still at the end of the day collaborating with the community and getting them centered around

the achievement of families, on growing adults.”

Holistic Treatment

Anderson points to a moral imperative in ensuring students in high-poverty districts are taught properly, tested soundly, treated in a holistic manner and prepared from an early age for college and career readiness — including for jobs in the school

district itself.

“If we use poverty as a reason why we can’t meet state standards, and the nation has more than 50 percent of its public schools students on free lunch,” she says, “what are we saying is going to

happen to those schools that face poverty conditions?”

Saying they can’t meet state standards is “scary,” Anderson adds. “The stronger statement is that we as school leaders who take on great challenges, we

are responsible for using systems thinking to help create a sustainable model to move beyond the issues that poverty presents.”

— LINDA CHION KENNEY

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement