The Leading Edge: Policy & Advocacy Blog

The Leading Edge, AASA's policy & advocacy blog, provides up-to-date information about activities in Washington, D.C. and Capitol Hill that affect you and your school district.

The Leading Edge, AASA's policy & advocacy blog, provides up-to-date information about activities in Washington, D.C. and Capitol Hill that affect you and your school district.

Topics include new or proposed regulations and federal policies, federal funding updates and opportunities, advocacy resources and more.

Latest Posts

-

April 24, 2024

USDA Releases Final Rule on Child Nutrition StandardsUDSA has released the final rule on child nutrition standards. Here's what you need to know.

-

April 19, 2024

PSLF and TEACH Grant Servicer ChangeThe Dept. of Education is making changes to the servicing of PSLF and TEACH grants that may impact some educators.

-

April 19, 2024

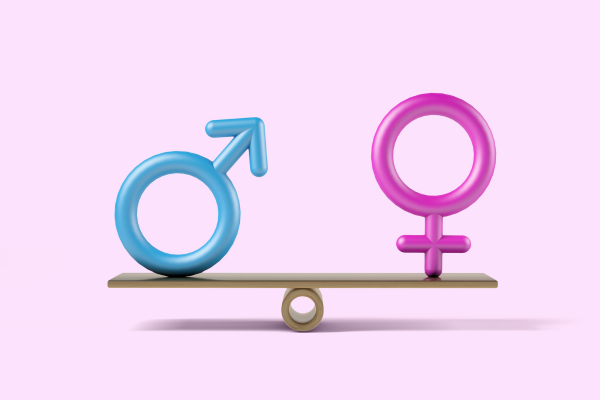

New Title IX Regulations Finalized- Effective Aug 1The U.S. Department of Education released revisions to Title IX on April 19, 2024. The amended Title IX regulations, which will be effective on August 1, 2024.

-

April 17, 2024

Opportunity Labs Invites Schools to Community of Practice for Mental Health SupportsOpportunity Labs, a national non-profit, is inviting school districts to apply to be part of a new Community of Practice, aimed at enhancing student mental health support against budget challenges.

-

April 16, 2024

Making the Most of Your Summer Fun(ds)—Creating Connections with Students and FamiliesThis is the eleventh installment of the Summer Funds series with AASA President Gladys Cruz.

-

April 16, 2024

AASA Joins National Organizations Endorsing COPPA 2.0AASA is pleased to endorse COPPA 2.0, as introduced by Senator Markey and others.

-

April 15, 2024

AASA Co-Hosts School Safety Briefing on Capitol HillOn Thursday, AASA was proud to co-sponsor “Smart School Safety: How Schools and Congress Can Maximize Investments for Kids” along with Sandy Hook Promise and the National Association of School Psychologists.

-

April 15, 2024

FAFSA Office HoursAs part of the FAFSA Week of Action (April 15 - 19), USED invites you to join USED staff for an office hours session for counselors, principals, school administrators, and school board members.

-

April 10, 2024

EPA Issues National Primary Drinking Water RegulationToday, the Biden Administration released a final National Primary Drinking Water Regulation for six PFAS – the first ever enforceable limit of so-called “forever chemicals”. This rule will directly impact districts that operate a non-transient, non-community water system (NTNCWS).

-

April 10, 2024

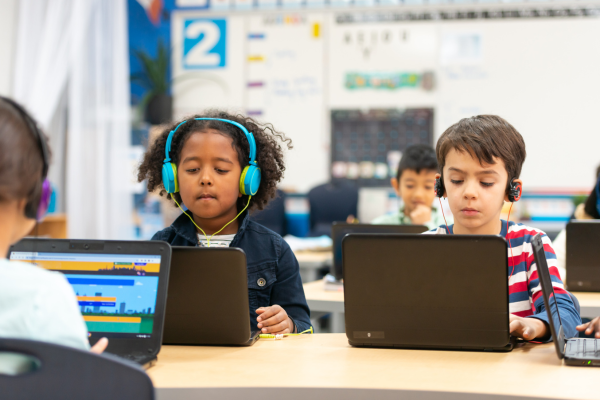

K12 Cyber and You: Ready to Go ResourcesWe have a list of resources from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in the Department of Homeland Security.

-

April 09, 2024

Community Sign-On Letter for Increased Labor-HHS-Education Funding in FY 2025The Committee for Education Funding is circulating their annual sign-on letter to secure a strong funding allocation for the House and Senate Labor-HHS-Education Appropriations Subcommittees.

-

April 05, 2024

ED and DOL Announce Additional Actions to Support Pathways Into EducationThis week, the Department of Education and Department of Labor announced actions to further expand access to high-quality and affordable pathways into education professions, including residency, grow your own, and Registered Apprenticeship programs. These actions include new funding and technical assistance.

-

April 04, 2024

The Advocate April 2024: What To Expect for FY 2025 AppropriationsNow that Congress has finalized Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 funding (see the full breakdown of that package here) – it’s time to immediately pivot to FY25.

-

April 02, 2024

USED Releases Guidance on Federal Property InterestLast week, ED issued guidance regarding the government-wide recording and reporting requirements for ESSER projects related to the acquisition or improvement of facilities with federal funds.

-

March 28, 2024

Making the Most of Your Summer Fun(ds)— Preparing Educators for a Great SummerThis is the tenth installment of the Summer Funds series with AASA President Gladys Cruz.

Latest Advocacy & Policy Resources

-

April 19, 2024

Superintendent Letter to Community Regarding 2024 Title IX RulesTopics: Advocacy & Policy, District & School OperationsUse this template letter to communicate to families in your district about changes to the Title IX Rules from the U.S. Department of Education. -

April 19, 2024

The 2024 Title IX Regulations - What Superintendents Need To KnowTopics: Advocacy & Policy, District & School OperationsYour AASA Advocacy team, Thompson and Horton LLP and ECR Solutions has created a helpful document of changes to the 2024 Title IX Regulations released on April 19. -

April 18, 2024

PEP Talk Episode 29: The School Voucher Legal SagaType:Podcast Topics: Advocacy & Policy, District & School OperationsOn this episode of PEP Talk, Kat Sturdevant interviews Jessica Levin, litigation director at the Education Law Center about the ongoing litigation of school voucher programs in states, and the rhetoric proponents use to justify the transfer of public funds to private institutions.

Receive legislative and regulatory actions direct to your inbox

Stay updated on the issues that matter most to you and understand how they could affect you, your district, your students and your community.